The Dream of What Could Be

How to listen beyond "good" and "bad"; and what I'm doing on this music blog

I’m feeling grim today—the warm weather has yet to appear and I think Instagram has gotten to me once again. I have been doing well with maintaining a fairly moderate intake of social media over the past few months, but every now and then the machinations of the music industry become a little too blatantly visible at a time when I’ve had too much coffee and too little sleep and I start to feel insane.

But if staring at socials is the most harmful thing I can do to my brain, which it might be, then writing this blog seems to be the best way of putting it back together. Even when a post doesn’t quite come together as well as I had hoped when I started it, I often have the feeling that I’ve carefully picked up all these sharp pieces of glass I’ve been cutting myself on for weeks or years and aligned them into… I don’t know, something like a sword?1

I’m not under any illusions that my little corner of the internet has any influence on anything, nor do I necessarily want it to—I suspect the moment people start reading me in any serious number would be the moment I no longer feel free to express myself in a pretty much uncompromising way.2

At the same time, my reach has been greater than expected, and artists seem to be responding well, which is already more than I was hoping for. I think the stakes of having the possibility that someone could read my writing about their music makes the writing stronger. I know it makes me scared to post every “roundup,” at least!

Today I want to say something out loud that has heretofore only been implied outside of footnotes: the one “rule” of this music criticism blog is to not criticize music. Which doesn’t mean that I’m not writing music criticism, because that is what this kind of writing is called, but that I’m only writing about music I can get behind, and I’m not interested in ripping into the flaws in someone’s art.3 As all of the money in the music market is slowly siphoned out by a confluence of financial incentives, it increasingly feels like the kind of bloodbath that sometimes happens in Pitchfork reviews (however tastefully stated, however accurate) is punching down on artists that don’t have the resources (read: money) to realize their dreams, while uplifting only the ones who do.

From the critic’s point of view, the response to this might go something like: “Well, if it’s not good, I can’t give it a good review. It’s too bad that there’s all this inequality out there, but what do you want me to do about it?” (*throws up hands*). Okay, but what if you look past what is good and is bad to see what could be?

I was sitting around the table with my housemates the other day and the question was raised: What are you best at? Good conversation starter. To tell you the truth, I don’t really do well with questions like this, in or out of job interviews, and my probably-ADHD brain ground to a halt. Imagine that—27 years old and no commodifiable skill-set. Who could have seen this coming?

Amy came to my rescue and reminded me that I am actually quite good at seeing the potential in things, or in people. This has actually always frustrated me and put me at odds with popular opinion: in music, for instance, I have always basically listened to songs’ idea of themselves, to what a song is trying to do, not necessarily what it is doing. Which is to say that at my core I’m more interested in the ideas than I am in the results. I hope you’ll believe me when I say this has made it incredibly hard to be an artist!

Even so, I think what the world needs perhaps most sorely right now is this way of seeing potential, which is to say an active imagination. I’ll keep my line of fire to the music world, and by that I generally mean the American music business, but I’m sure you could extrapolate my argument into politics if you wanted to.

Anyway, in the music industry of, say, the 90s, when the big labels were pumping money into bands they thought would be the next big thing, it may have made a kind of sense to lob scathing criticism at these bands who were handed $100,000 to make their big, terrible-sounding rock record. “Selling out” used to be the worst insult among fans; now the sexiest thing an artist can do is give themselves up to any label that will have them. The “DIY” movements that actually birthed many of the bigger artists today may have been cool at the tail end of the 00s, but have now been basically disempowered and forced out of existence through rising rents and dried-up revenue streams. “DIY” is now synonymous with “local band” which—have you noticed?—has become a dirty word, usually prefaced with “shitty”.

But if it’s impossible to make it unless you… are rich, where do you expect the next generation of music to come from? I guess I don’t have to answer that question.

So it doesn’t make sense to me to write criticism like a critic anymore. Criticizing Pavement for spending a fortune making a mediocre record in 1999 is one thing (and I’m not sure I even agree with the value of that, but whatever). Criticizing a band for doing their utmost to make a great record but falling short for lack of time, resources, or time and resources to develop their talent enough to make their music more accessible—feels like a waste. But if you stop evaluating what is good and what is bad and start listening for what could be, you’ll notice that there are plenty of records in recent years that are actually doing the thing, however humbly, and that contain within them the same seeds of greatness that flowered (sorry) into the big pop records we all know and love.

One of my professors in college, the composer Andrew Greenwald, taught a music/philosophy class called “New Modes of Listening” for a semester. It was a wild ride. We tried to read a ton of theory and have opinions about it. The students rebelled! Why read all this “heady” material? What did any of it have to do with music? How does reading Baudrillard make me a better composer? Andrew pushed back. One of the things he said stuck with me, which was that (if memory serves) these texts are like hallucinogens: reading them does actually expand your consciousness and change the way you see the world. They may make you have to work for it, but the work is perhaps part of the brain-expanding bargain, and once you’ve done it and understood what there is to understand, you’ll be more open to doing that kind of work in the future.

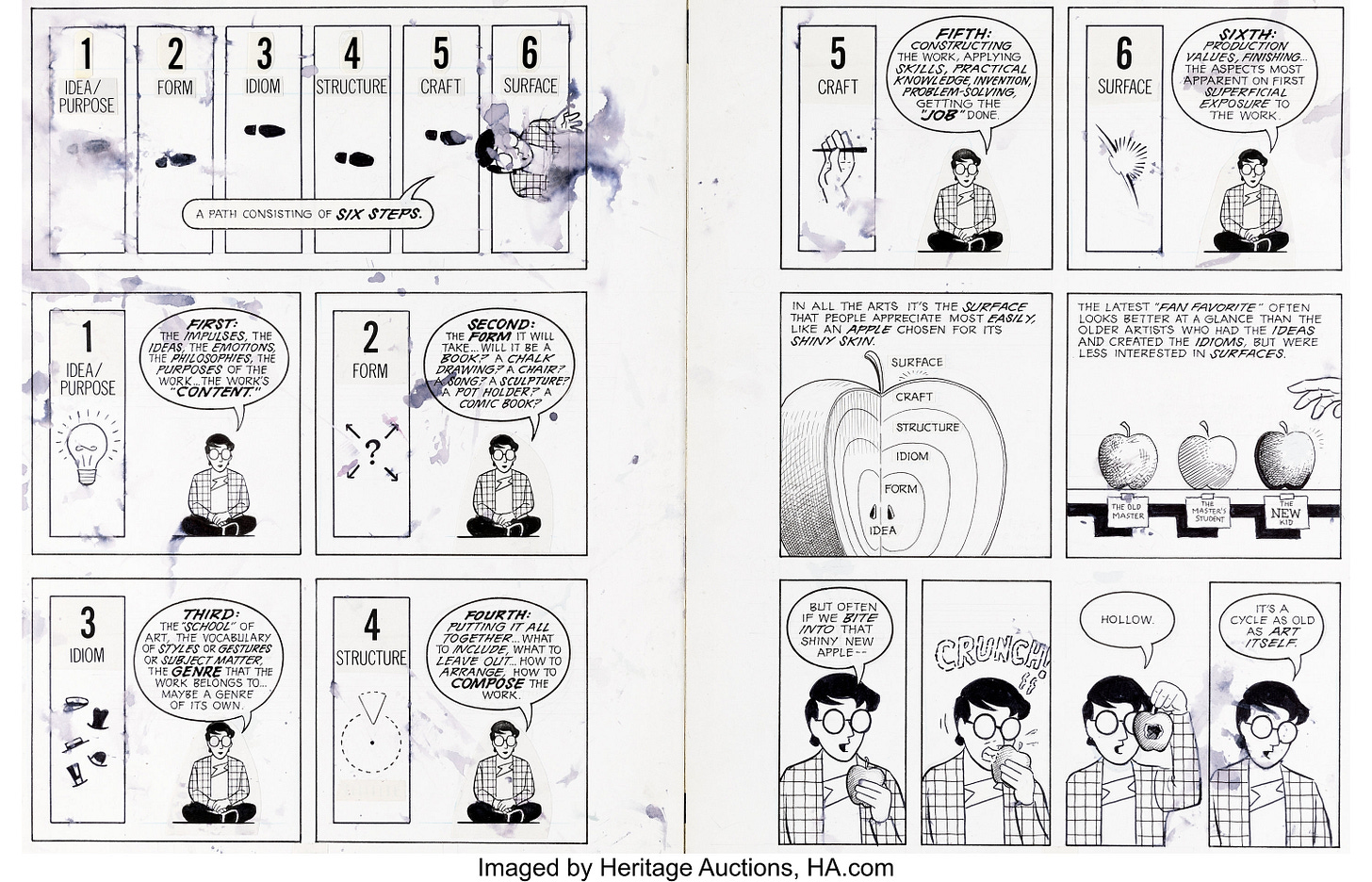

Here, then, is a New Mode of Listening. What I have been doing here, I think, is trying share with you the way that I hear things, where the idea is of paramount importance, and the form, idiom, structure, craft follow from there. Funnily enough, I’m not the only one to think this way…

Okay, well, this is at risk of becoming a manifesto, which was not really my intent.

I just wanted to say that I sincerely appreciate everyone who’s been reading and responding to this stuff, because it makes me think that I might be, maybe, on to something.

The goal here is to connect the old music to the new, and to explore some avenues that were unexplored in their time, but could be again—yes, I’m saying lost futures, again. I want you to know how the new song by so and so is good because it’s grounded in a much older convention, but it’s also good because it’s pushing that convention forward. In fact, I want you to know about all the artists that I think are doing amazing work, which you’ll be able to hear if you can hear past the surface-level. In other words, I’ll be uplifting the underdogs, but also talking about the major players whenever I feel they are relevant—and so you will see that the two are in fact the same underneath, separated only by the facts of life: opportunity, privilege, luck.4 You may even see how the “underdogs” often have stronger ideas, even if their surfaces are less shiny.

I don’t expect to be very successful in doing this, because it’s basically biting the hand that feeds.5 On the other hand, I’m free to do as I please—my writing is not compromised by any special interest, except maybe being interesting. And the great thing about ideas is that they are potentially highly contagious. Feel free to spread mine around.

“I was not born to live a man's life, but to be the stuff of future memory. The fellowship was a brief beginning, a fair time that cannot be forgotten. And because it will not be forgotten, that fair time may come again. Now once more, I must ride with my knights, to defend what was... and the dream of what could be.”

- King Arthur, Excalibur (1981)

—

Thanks for reading, I’ll see you next week for either more new music or a thorough evisceration of the phrase “once in a generation talent”.

Or a window, or a lens, if we want to get a little more Bennington.

Until then… the emporer is naked!

As I’ll say in a moment, I might be up for ripping into the flaws in their art’s central idea, but I won’t because if I had a problem with that then I wouldn’t consider writing about them in the first place. Unless, idk, you pay me or something.

As one of my favorite bloggers, Shamus Young, so effortlessly and elegantly put it: “There is no good or bad luck, only the steady unrolling of random fortune, which is a heady mix of heartache and mercy.”

I just heard a great take from internet troublemaker Caleb Gamman that went something like: celebrities are always cowards and never interesting because in order to become and remain a celebrity you cannot actually be opposed to power, in fact you must always be subtly sucking off power. Even, or especially if, your brand is “anti-establishment”-themed.